Active recovery for Standardbreds is currently under-explored in equine research. However, for human athletes, numerous studies demonstrate the importance of this recovery post-exercise. The ability to recover is even more crucial as it is an indicator to assess the fitness level. The better the recovery is, the better the fitness is. Trainers should not neglect this step during training.

What are the best practices in terms of recovery?

1. Measuring and qualifying the Standardbreds’ recovery

Several parameters qualify the recovery quality. First of all, cardiac and respiratory recovery are essential to assess the recovery of Standardbreds. First, the heart rate and speed curves analysis is a reliable tool for evaluating recovery capacity.

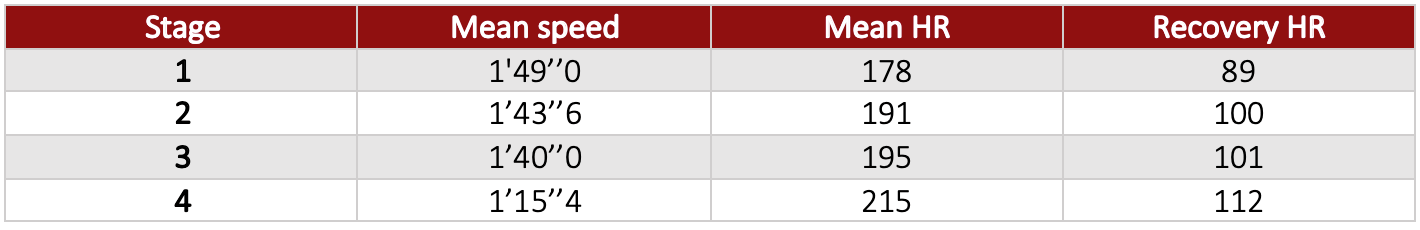

Here is an example of recovery analysis using Equimetre data. This horse’s training consists of 4 straight 1000m intervals with recovery phases between each interval.

Data from the EQUIMETRE platform

On average, this horse has a post-interval heart rate of 100 BPM. It indicates an efficient cardiovascular system. Indeed, recovery can be described as usual when the heart rate measured between intervals falls below 110 BPM.

Secondly, the ability of the body to eliminate the lactic acid accumulated in the bloodstream indicates a high level of fitness. From one session to another, recovery can improve. We can see it with a comparable effort if the post-exercise HR decreases.

When followed carefully and daily, recovery is a crucial parameter for sports preparation and health monitoring. Unexplained deterioration in recovery may be a symptom of cardiorespiratory pathologies. A veterinarian should investigate it. He can use EQUIMETRE information with the electrocardiogram (ECG) collected during training to refine his diagnosis.

2. Active VS Passive recovery

The horse’s body must regenerate its physical and physiological resting conditions as quickly as possible to reduce the time interval between each training. Post-exercise recovery must therefore be as effective as possible. There are two types of recovery: passive recovery and active recovery.

Passive recovery, a model adapted to alactic efforts

This recovery consists of doing nothing particular after the effort. At most, a little walk to get back to the stables. It is efficient after low intensity or low-speed endurance exercises during which the body does not produce lactic acid.

During a low-intensity effort, there is no oxygen debt. It is the oxygen supply necessary to return to the physical and physiological conditions of rest. This debt is also called ” recovery oxygen consumption”.

For information, there is generally no lactates accumulation when the oxygen consumption is less than 50% of the VO2 max. In this case, a passive recovery would better suits the situation. Indeed, the exercise would only serve to raise the metabolism (producing new lactates). As a result, it will delay its elimination and the horse’s full recovery.

The active recovery benefits after an anaerobic lactic effort for standardbreds

A standardbred race lasts between 2 and 5 minutes, covering between 1,600 and 4,000 meters. Therefore, the aerobic system mobilization is not sufficient to provide the necessary energy. On average, the effort is at 50% in the aerobic zone at the beginning of the race. Then, 50% of the race uses the anaerobic lactic zone to reach the maximum speed during the final sprint.

One of the solutions to eliminate the accumulation of lactic acid is active recovery. During recovery, the body eliminates the metabolic waste and restores the energy reserves. Training also helps to tolerate the presence of lactic acid and to lower its level more quickly and efficiently. The amount of lactic acid present depends on the intensity and duration of the effort.

After exercise, maintaining an activity that promotes blood circulation and oxygen supply helps to improve recovery. It means doing aerobic (endurance) effort immediately after a relatively short, intensive effort to help your horse recover. For example, 10 minutes of light trotting is active recovery. The objective of this recovery is to return the horse to resting conditions as quickly as possible. As a result, horses are ready for a potential future exercise. An active recovery exercise (such as trotting) the day after an intense effort can also help. It will complete the elimination of waste products. The complete restoration of the muscle takes place between 24 and 48 hours after the intense effort (depending on the horse).

3. What the science says: the benefits of active recovery

Few scientific studies have focused on the active recovery analysis for horses, but they mainly studied Eventing horses. Regarding standardbreds, a veterinary thesis by Sandra Dahl, at the National Veterinary School of Alfort, highlights the various benefits of active recovery for standardbreds through her experimental study.

The study involved 37 horses between the ages of 3 and 11 years who performed an exercise test consisting of three successive three-minute intervals (with speed increasing from one interval to the next), each separated by one minute of rest. The goal was to exceed the 4 mmol/L lactate threshold at the end of the last interval (which is synonymous with an intense effort). Following this work, each of the four groups performed a different recovery:

- Passive recovery (direct return to the box after effort)

- Light active recovery (10 minutes of walking after effort)

- Medium active recovery (10 minutes of slow trotting after effort)

- Intense active recovery (10 minutes of trotting after effort)

We will present the results of the passive recovery group and the intense active recovery group.

Post-exercise heart rate recovery is better

Ten minutes after exercise (at T20), i.e. 10 minutes after active recovery and 20 minutes after passive recovery, the heart rates of the two groups of standardbreds are almost similar. For the horses that performed passive recovery, the HR almost did not decrease since the T10 time point, stabilizing around 75 BPM. However, for the group that performed active recovery at a 25 km/h trot, the heart rate decreased from about 160 BPM to about 60 BPM between T10 and T20. Thus, active recovery allows a faster return to a heart rate close to the resting one. At T60, 50 min after the active recovery, the average heart rate of the group that benefited from an active recovery at a trot of 25 km/h returned to its resting value and was significantly lower than that of the group that recovered in the stall.

Graph showing the heart rate of horses (mean ± standard deviation), by recovery group

Source: Sandra Dahl’s veterinary thesis on active recovery for standardbreds

Regarding cardiac recovery, an active and intense recovery (trotting at 25 km/h) seems more relevant than passive recovery, or a light trot (15 km/h).

A faster return to normal temperature

Horses that have actively recovered see their body temperature return more quickly to a value close to that of rest (38.5° after recovery versus 39° when returning to the stall directly after exercise).

Graph showing the body temperature of horses (mean ± standard deviation) by recovery group

Source: Sandra Dahl’s veterinary thesis on active recovery for standardbreds

Finally, the practice of active post-exercise recovery facilitates lactic extraction from the bloodstream. However, we can identify some limitations to this study. First, we can question the reliability of the tools used during the research, and this veterinary thesis has no scientific validation. Furthermore, the test didn’t consider the different weather conditions to analyze horses’ performance. Finally, the research compared various horses with different capacities. A comparison by horse, with and without an active recovery, would be more relevant.

4. Evaluating the best recovery option for your horses

As you can see, to identify the most suitable recovery method, you should measure the intensity and duration of the effort. To do so, we can quantify the training with EQUIMETRE. If the exercise takes place in the anaerobic zone, active recovery may be relevant.

It is possible to measure the effectiveness of active recovery on standardbreds. We can carry out an effort test, with three intervals of 3 minutes each with a resting period of 1 minute between each interval. Following this, horses can perform an active recovery at 25km/h to test its effectiveness. During this test, it is necessary to measure the heart rate with a heart rate monitor such as EQUIMETRE.

You should perform these measurements at T0 (directly after exercise), T10 (at the end of active recovery), T20, and T60 (at rest). It is interesting to perform the same test on the same horse without active recovery after exercise. In this way, we can measure different recovery rates and know precisely if active recovery is beneficial after intense training for one specific horse. However, these sessions are very demanding and should be conducted with caution and with the help of a veterinarian.

Conclusion

The more standardbreds performed active recovery, the more post-exercise discomfort and pain can be reduced. Therefore, it may be recommended that trainers perform active recovery within 10 minutes of intense exercise. On the other hand, such effort is not recommended after low-intensity training, as it would produce new lactates to be eliminated and would be counterproductive.

However, the lack of specialized scientific studies for standardbreds does not allow us to affirm with certainty the benefits of active recovery. Equine research should explore new studies to confirm the benefits noted in Eventing horses.

Active recovery is beneficial during very intense efforts, during which the body produces lactic acids. The benefits are multiple: elimination of lactic acids, improvement of cardiac and respiratory recovery, and reduction of body temperature to return to normal.

Keywords: active recovery, standardbreds, heart rate, body temperature, efforts, race horses